Not Another "Why I Like Tailwind" Post

As previously advised, don't listen to me because I do not know what I think or what I am doing. So for my first foray into this type of webdev writing, I'm gonna cover a modern classic: the Tailwind take.

There are already too many of these posts (and rebuttals, and rebuttals to the rebuttals) to the point that they have become the "Anyway, here's Wonderwall" of dev articles. I'm not sure if there's a lot left to say, but this is a loud, crowded venue and I've gotta play something so, anyway, here's Wonderwall.

One "framework" to rule them all?

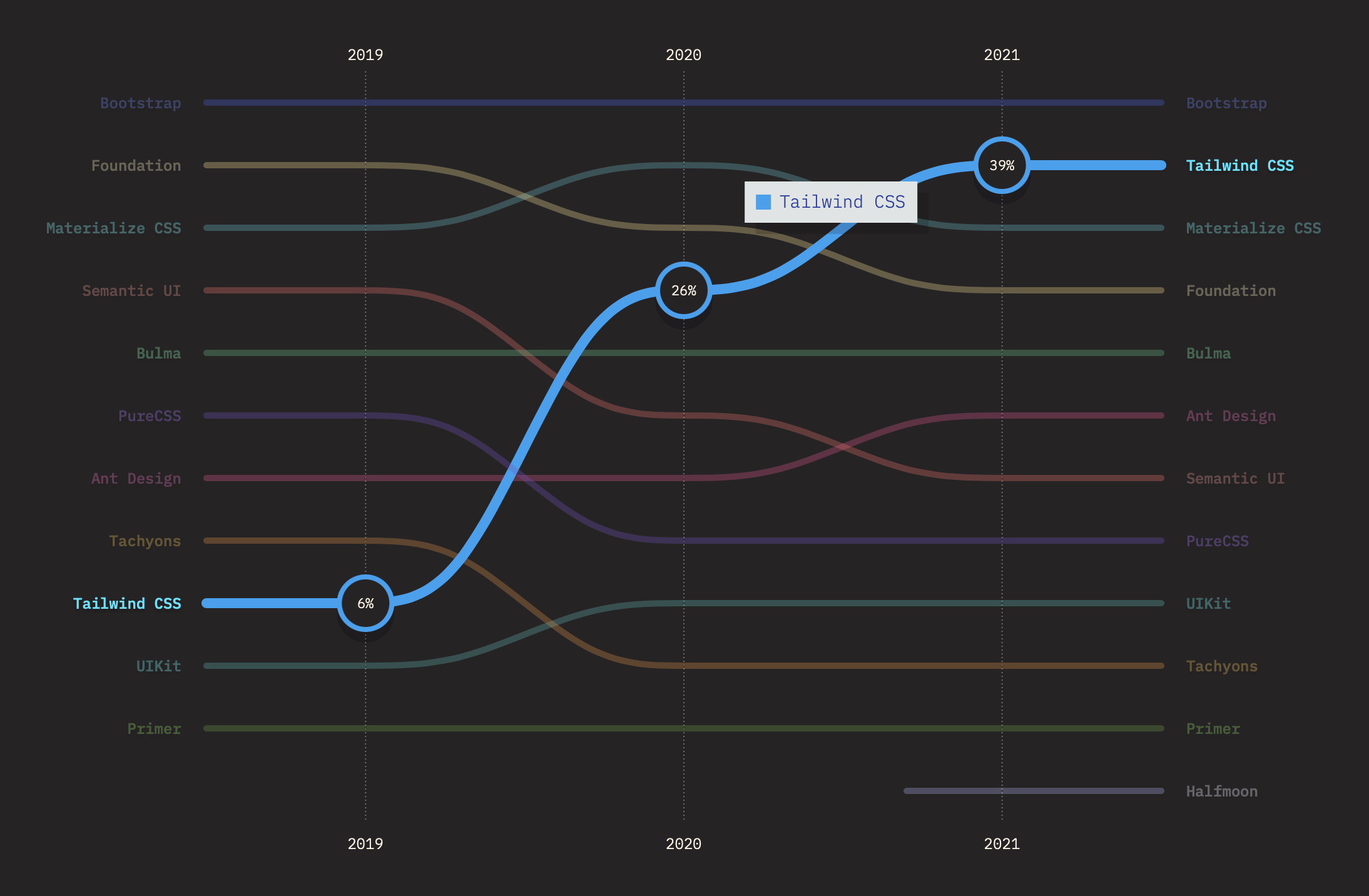

Tailwind is fast becoming the dominant CSS "framework" (see chart below), though I think "framework" is a bit of a misnomer. I think it's really more of a utility library.

Library: "Here are some tiny building blocks." vs. Framework: "Here are some components that you can re-skin."

The Tailwind team (or maybe just whoever wrote the copy for their new site) calls it a "utility-first CSS framework", but I think that's just a word-of-least-resistance.

In my mind, a "framework" is opinionated to the extent that you stop having to think about composing an interface and skip right to thinking about content and style. As an example, I would expect a framework to have a .btn class built in, while a utility library would force you to compose a .btn class or component using utility styles.

One could argue that the preselected colors, spacing units, and shadows that Tailwind creates are constrained enough to warrant using the term "framework", but with tailwind.config.js and the new arbitrary values feature, we are sort of outside the realm of a framework and really just doing "inline styles on steroids (i.e. media queries and pseudo elements allowed) + some constraints".

Enough about semantics

JK semantics are really fun and important actually. But let's get to what I like I about Tailwind:

The pros, in short:

Let's dive a little deeper:

Reducing complexity when debugging

Let's say you've got a modal component and you can't figure out why the hell your "Close Modal" button is being obscured by some other piece of content on the page. It's probably a z-index thing, but you're not sure so you go hunting in some css files.

With Tailwind, there are two reasons why you might find the issue more quickly:

-

You probably don't have to open another file.

All of your classes are right there in the HTML. Sure, you may have to open another component or template, but that's the case no matter what. You are at least removing one place for the bug to hide.

-

You have a limited set of

z-classes that could be in play.There are only 5 (unless you use arbitrary values)

z-classes, all with fairly low values so it should be pretty easy to search your codebase for those classes and find the conflict. Noz-index: 9999here.

Speed of composition

Maybe it's just me, but being able to compose my HTML and start styling in the same file means I can create layouts fluently. The feedback is more immediate and there is no file-switching to slow me down.

Performance

This comes up in almost every article on Tailwind but it bears repeating: Tailwind when used properly will reduce the size of the CSS you ship. The main reason for this is that in a non-Tailwind project you will almost certainly write display: flex close to a bajillion times. That is unnecessary bloat in the size of the css (though I am sure this could be solved by some CSS-in-JS strategies or code splitting).

Cons

The cons, in short:

Ugly, long class lists

It's just simply objectively uglier to look at:

<section class="md:p-8 dark:bg-blue-100 dark:text-blue-100 p-4 text-blue-100 bg-blue-900"></section>

than:

<section class="section section--blue"></section>

And all of those classes can start to look like alphabet soup. I have recently started using the Headwind VS Code extension that helps auto-sort the classes to make your class lists more consistent and legible.

📌 Update: Check out my new post on Headwind here.

The inevitable "Bailwind"

Behind every good Tailwind project is a sad "bailwind" file. A.k.a. a junk drawer with all the random styles that just don't fit, or classes that regenerated by a CMS (e.g. .shopify-policy__title to target the legal pages in a Shopify theme or a .wp-block class in a Wordpress theme).

The "con" here is just that this is one more place to look to debug your CSS. Let me suggest that if this file gets sufficiently big you might want to rethink using Tailwind on that project.

Obscuring vanilla CSS

In my day job, I lead a small dev team that includes two other, more junior devs. For the most part, I get to decide on the technologies we use. So when I chose Tailwind for our main projects, I was nervous that I was basically teaching them a foreign language, but only the slang. Or teaching them how to paint like Jackson Pollock while skipping Intro to Light and Shadow.

It might be that focusing so much on Tailwind and its shortcuts (like scale-110 ) might obscure what the underlying CSS properties at play really are (transform: scale(1.1)). I even see it with myself when I Inspect Element and I've only been dealing with Tailwind classes all day, I start to have brain farts where I type items-center instead of align-items: center.

There is also a tendency, for me at least, to assume that any Tailwind class has nearly-full browser support. If you are using Tailwind in Chrome, you are living in the best-case scenario and as developers, it is not our job to write code for the best-case scenario. Not all browsers support scroll-behavior: smooth or ::marker, but you might forget that if you are using Tailwind. I think it's still the right call to include these widely-but-not=fully-adopted properties because they are good and gracefully fail, but more than once it has tripped me up so I wanted to include it.

All in all though, I feel like this is simply something to watch out for and take time to understand which CSS properties each class is utilizing.

Conclusion

Tailwind is a useful abstraction on top of CSS that helps developers quickly compose layouts. The pros outweigh the cons but I am open to changing my mind. Specifically, I'd love to work on some larger-scale projects to see how really big codebases might handle it.

If you made it this far, God bless you child. And hope to see you next time.